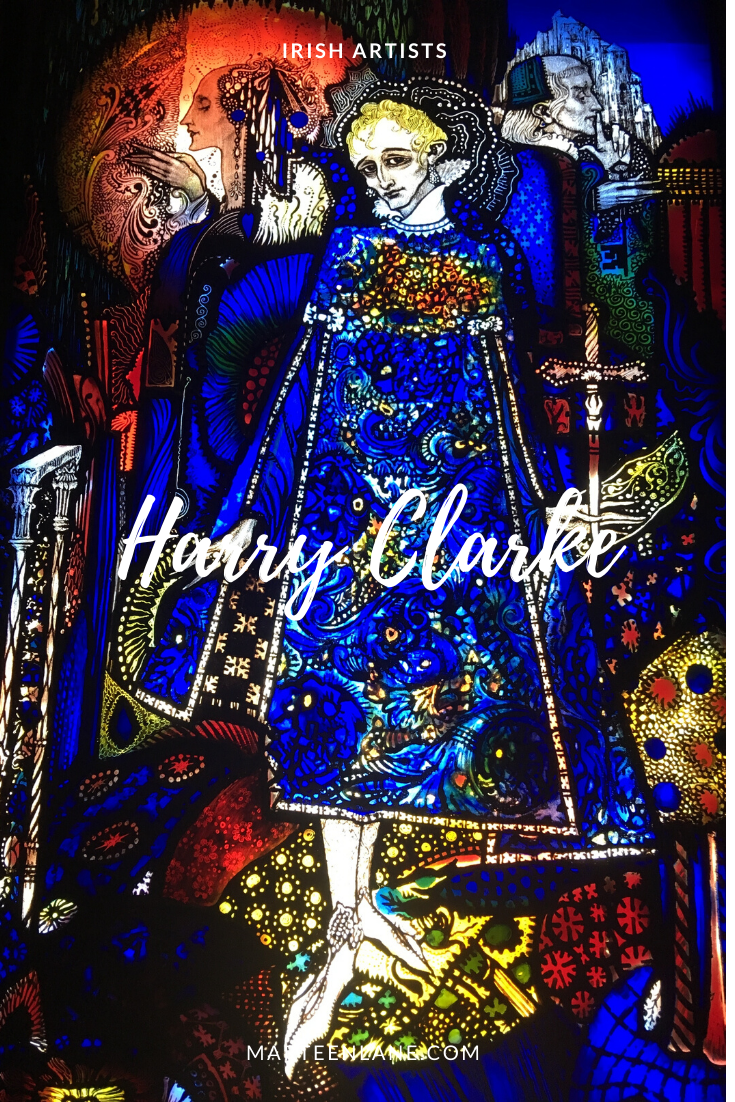

Harry Clarke is an Irish artist I came across many years ago and thanks to my younger brother John fell in love with his work. St. Mary’s RC Church, in my hometown of Ballinrobe in Co. Mayo is lucky enough to have nine Harry Clarke Windows and draws visitors from all over. We have local historian Averil Staunton to thank for her work on the windows in the church in Ballinrobe. If you’re a fan of Harry Clarke’s works you need to get yourself to Ballinrobe and look for the Harry Potter window 😉 No matter how many times I see Harry Clarke’s work it still takes my breath away. To me, that’s the mark of an incredible artist. Although ‘incredible’ is an understatement; the fine detail, the jewel-like colours, the subject matter makes him the ‘strangest genius’.

Biography

Harry Clarke was born in Dublin on 17 March 1889 to Joshua and Bridget (neé MacGonigal) Clarke. His father Joshua was a well-known church decorator originally from Leeds in England (Gordon Bowe, 2012). In 1892 Joshua’s business, Joshua Clarke & Sons, expanded into stained glass. Harry grew up on North Frederick Street with a studio at the back of his home. As a young boy, he attended Marlborough Model School and later the Jesuit Belvedere College. At Belvedere College Harry received a very strict religious education focused on hell and damnation. It is thought that this overzealous religious indoctrination had a profound effect on the sensitive Harry and is reflected in his art, particularly his illustrations (Costigan & Cullen, 2010). At fourteen years old Harry suffered a terrible blow, when his mother Brigid, only forty-three years old, passed away. Brigid was consumptive and Harry and his older brother Walter inherited a weak chest from her (Gordon Bowe, 2012). A year after his mother’s death, Harry left school and became an architect’s apprentice. This was short-lived as he became an apprentice in his father’s studio in 1905 (Costigan & Cullen, 2010).

Harry began formal training in stained glass at the age of fifteen at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. He was under the tutelage of A. E. Child, an English craftsman, and manager of An Túr Gloine (Costigan & Cullen, 2010). While studying at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, Harry’s father Joshua organised for him to attend the South Kensington School of Design while working in a London firm for a trial period of three months. Joshua thought his son’s work in Dublin showed a lack of experience but was carried out with great effort, order and assurance (Gordon Bowe, 2012). In 1911, now living back in Ireland, Harry won his first of three consecutive gold medals for his window The Consecration of St. Mel, Bishop of Longford, by St. Patrick (see Figure 1) in the National Competition held in South Kensington. On winning a travelling scholarship from the Board of Education he travelled to France in 1913 to view the stained glass windows of the cathedrals and churches there. These wonderful windows greatly influenced him to use rich, jewel-like colours in his future work with stained glass. Harry completed his studies at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art in 1913 (Costigan & Cullen, 2010; Dowling, 1962).

Work

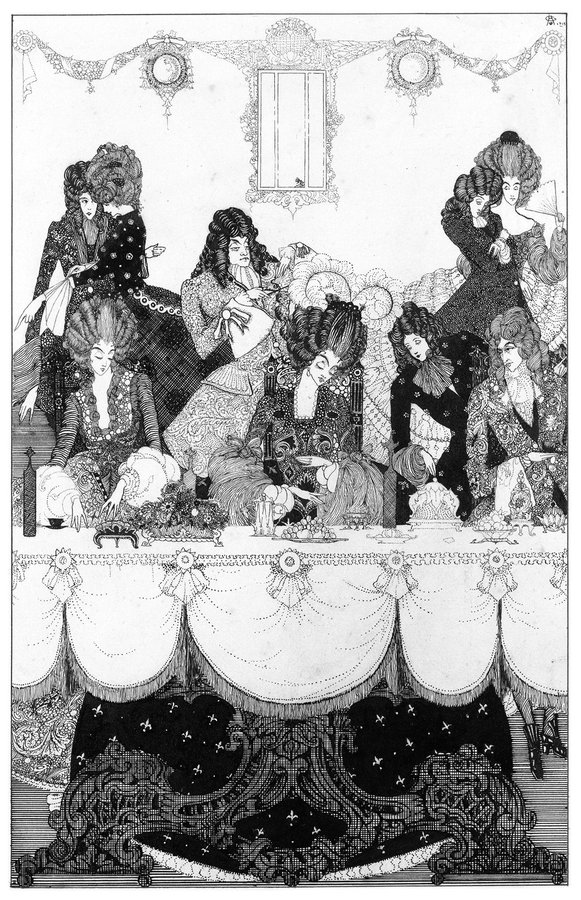

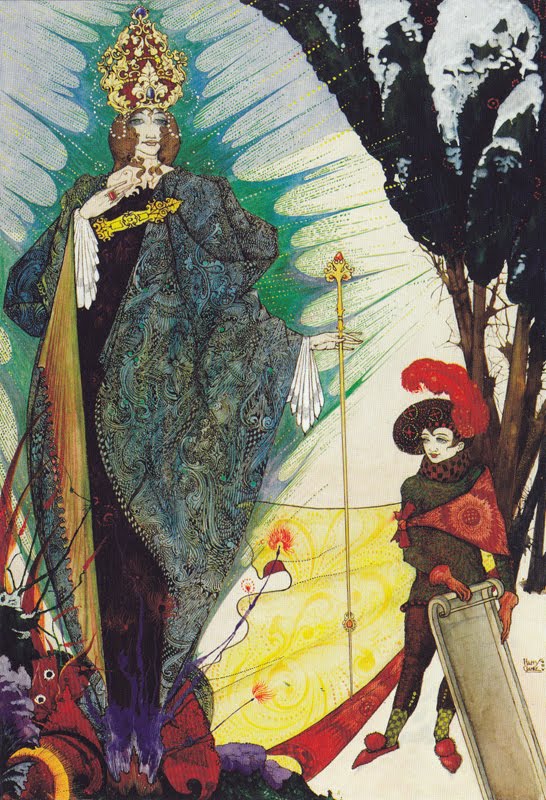

Laurence Waldron, a stockbroker, Nationalist MP, Governor of the National Gallery of Ireland and Governor of Belvedere College, would be very influential to Harry. As his patron Waldron gave Harry his first commission in book illustration in 1913, to illustrate The Rape of the Locke by Alexander Pope (see Figure 2). These illustrations have been described as whimsical, wistful, and flimsy while verging on boring (Costigan & Cullen, 2010; Gordon Bowe, 1983). That same year Harry moved to London in search of a publisher for his book illustrations. After several rejections, he secured a commission from George G. Harrap to illustrate the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen (see Figure 3). Harry noted in his diary that each illustration took him seven days to finish. He completed his commission of Andersen’s fairy tales in April 1915 by adhering to a strict schedule (Costigan & Cullen, 2012; Kelly, 2011). Riding on his great success Harry secured more commissions to illustrate the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Charles Perrault, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and many others. His illustrations involved suggestive and wanton sexual imagery that tended towards the outlandish and indecent (Costigan & Cullen, 2010).

One special commission was his illustrations for the impeccable and emotional Ireland’s Memorial Records 1914-1918 (see Figure 4). It was a book listing the names of the fallen Irish men who served in World War I, as compiled by the Irish National War Memorial Committee. The Memorial consisted of eight volumes and was beautifully printed by Maunsel and Roberts in 1923 (Helmers, 2016; Gordon Bowe, 1983). Harry’s illustrations for the Memorial included the title page, with a youthful Hibernia surrounded by Irish symbols; eight borders throughout the books; and a single cross to finish the final page of each volume. He incorporated Celtic, non-Baroque and Art Deco motifs into the illustrations, with silhouetted battle scenes, medals, and religious and mythological themes. He was very much influenced by cinema and the revival of Celtic art, illustrating the modern and the traditional (Helmers, 2016; Gordon Bowe, 2012). Harry’s illustrations for the Memorial were nearly forgotten as a feeling of negativity arose from the political upheaval and conflict in Ireland (O’ Riordan, 2016).

Of course, Harry is best remembered for his stained glass work. Religious iconography was mainly depicted in his windows, which was in stark contrast to his dark and sexual illustrations (Costigan & Cullen, 2010). Harry’s first major commission for stained glass was in 1915 for the Honan Chapel in Cork, in which he designed eleven windows. The chapel was newly built in the Hiberno-Romanesque style and was to be decorated with the work of Irish artists. Harry’s position as a stained glass artist of excellence was secured. His use of colour and his imaginative representation of the religious subjects was noted (see Figure 5). Commissions were rolling in and Harry continued to produce high-quality stained glass work (Dowling, 1962; Costigan & Cullen, 2010).

In 1925, Harry was approached by the Irish Government to design a stained glass window as a gift from the Irish Free State to the League of Nations in Geneva. The Geneva Window (see Figures 6) consisted of eight panels portraying scenes and excerpts from the literature of some of Ireland’s best writers, including William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, Lady Gregory, and J. M. Synge. Harry wanted to show Ireland’s literary genius to the world through his work on the window (Costigan & Cullen, 2010; Gordon Bowe & Mulcahy, 2013). Despite his best efforts, the window was rejected. The president of Ireland, W. T. Cosgrave, felt that the image of Ireland Harry was portraying was not one the government was happy to have on show. The writers Liam O’ Flaherty and James Joyce were of dubious morality, while the character Joxo from Sean O’ Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, was depicting Ireland as a land of drunks; not to mention the half-naked women and young lovers exuding lust and passion (Costigan & Cullen, 2010; Canavan, 2011). The window was never given to the League of Nations nor was he paid for his hard work until after his death. It was locked away, out of sight out of mind, until 1932 when his widow Margaret bought it back from the State. The window is now on display in the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, Florida (Costigan & Cullen, 2010).

Styles & Influences

Harry took from many different styles and influences, molding his own unique style. Many Irish writers and artists, such as Lady Gregory, George Russell (AE), J. M. Synge, and William Butler Yeats, were influenced by the Celtic Revival Movement. Irish mythology and folklore were central themes to their work. This was to elicit a feeling of pride in the Irish people for their cultural heritage. Art Nouveau began to appear in Europe from the 1870s to 1914. Creeping plant motifs and elongated feminine forms were common images of the Art Nouveau style. The influence of Art Nouveau can be seen in Harry’s Our Lady and Child adored by St. Aidan of Ferns and St. Adrian (1919) (see Figure 7). Symbolism spread throughout Europe in the late nineteenth century and was inspired by themes of mythology and folklore. While Harry already had a preference for wondrous themes, symbols of beautiful damsels, princely heroes, and monstrous demons were even incorporated into his church windows. He is constantly compared to the English symbolist illustrator, Aubrey Beardsley, whose own work reflects the erotic and grotesque. A very different style of art came to the fore in the mid-1920s. The Art Deco style focused on sleek geometric forms with garish colours. The window of the Sacred Heart, St. Margaret Mary and St. John Eudes (1919) (see Figure 8) would be a great example of the Art Deco influence in Harry’s work (Costigan & Cullen, 2010).

Conclusion

Harry died after many years of ill health on January 6 1931 in Coire, Switzerland. He left a lasting impression on the art world, having created over 160 stained glass windows for church and commercial commissions, as well as a number of striking panels for private patrons. Even new generations are discovering Harry through his book illustrations (Costigan & Cullen, 2010). He created a unique style that has been described as part beautiful, part complicated, part unhealthy, but as a whole unwholesome and intricate. Gifted with colour and a genius with stained glass, Harry’s dreadfully short life deserves to be remembered (Gordon Bowe, 2012).

Have you seen any of Harry Clarke’s stained glass work in real life? What do you think of his works? I’d love to hear from you!

Bibliography

Canavan, T. (2011). ‘The Loveliest Thing Ever Made By An Irishman: Harry Clarke’s Geneva Window. History Ireland. Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 34-35.

Costigan, L. & Cullen, M. (2010). Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke. Dublin: The History Press Ireland.

Costigan, L. (2015). Harry Clarke Stained Glass. [Online] Hyperlink http://www.harryclarke.net/ Accessed 12th March 2018.

Dowling, W. J. (1962). Harry Clarke: Dublin Stained Glass Artist. Dublin Historical Record. Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 55-61.

Gordon Bowe, N. (2012). Harry Clarke: The Life & Work. Dublin: The History Press Ireland.

Gordon Bowe, N. (1983). Harry Clarke: His Graphic Art. Mountrath: Dolmen Press.

Gordon Bowe, N. (2006). A Regal Blaze: Harry Clarke’s Depiction of Synge’s “Queens”. Irish Arts Review. Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 96-105.

Gordon Bowe, N. & Mulcahy, J. (2013). Harry Clarke’s Geneva Window. Irish Arts Review. Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 118-127.

Haggerty, A. J. (1999). Stained Glass and Censorship: The Suppression of Harry Clarke’s Geneva Window, 1931. New Hibernia Review. Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 98-117.

Helmers, M. (2016). Harry Clarke’s War: Illustrations for Ireland’s Memorial Records 1914-1918. Sallins: Irish Academic Press.

Helmers, M. (2015). Shadows of the Dead: Harry Clarke and Ireland’s Memorial Records 1914-1918. Éire-Ireland. Vol. 50, No’s. 3 & 4, pp. 7-34.

Kelly, S. (2011). A Promising Illustrator. Books Ireland. No. 333, p. 178

Kelly, O. (2015). Scandalous Harry Clarke Window Goes on Display in Dublin Gallery. Irish Times. [Online] Hyperlink https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/visual-art/scandalous-harry-clarke-window-goes-on-display-in-dublin-gallery-1.2135844 Accessed 12th March 2018.

O’ Byrne, R. (2007). Cool Reception for Harry Clarke’s Illustrations. Irish Arts Review. Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 52-53.

O’ Riordan, A. (2016). Harry Clarke’s Illustrations of War and Tragedy are Forgotten No More. Irish Examiner. [Online] Hyperlink https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/artsfilmtv/harry-clarkes-illustrations-of-war-and-tragedy-are-forgotten-no-more-374371.html Accessed 12th March 2018.

Staunton, A. (2013). Harry Clarke’s Liquid Light: Stained-Glass Windows of St. Mary’s Church, Ballinrobe. Ballinrobe: Ballinrobe Archaeological and Historical Society.

Sullivan, K. (2012). Harry Clarke Modernist Gaze. Éire-Ireland. Vol. 47, No’s. 3 & 4, pp. 7-36.

White, J. et al. (1968). Irish Stained Glass. Dublin Historical Record. Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 225-226.

Images

Geneva Window (Harry Clarke, 1930, Wolfsonian Museum). [Online] Hyperlink http://www.harryclarke.net/geneva_home Accessed 12th March 2018.

Harry Clarke Portrait. [Online] Hyperlink https://www.wikiart.org/en/harry-clarke Accessed 3rd January 2020.

Ireland’s Memorial Records 1914-1918 (Harry Clarke, 1923). [Online] Hyperlink https://rcsiheritage.blogspot.ie/2014/06/irish-soldiers-lost-in-wwi.html?view=flipcard Accessed 12th March 2018.

Our Lady and Child adored by St. Aidan of Ferns and St. Adrian (Harry Clarke, 1919, Church of the Assumption, Wexford). [Online] Hyperlink https://www.pressreader.com/ireland/gorey-guardian/20180918/282269551306236 Accessed 3rd January 2020.

Sacred Heart, St. Margaret Mary and St. John Eudes (Harry Clarke, 1919, Vincentian Fathers Church of St. Peter, Dublin). [Online] Hyperlink http://www.harryclarke.net/phibsborough_home-147 Accessed 12th March 2018.

St. Finbarr (Harry Clarke, 1916, The Honan Chapel of St. Finbarr, UCC, Cork). [Online] Hyperlink http://www.harryclarke.net/honan_chapel_cork_st_finbarr Accessed 3rd January 2020.

The Consecration of St. Mel, Bishop of Longford, by St. Patrick (Harry Clarke, 1910, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork). [Online] Hyperlink http://www.harryclarke.net/crawford-_p1 Accessed 12th March 2018.

The Rape of the Locke by Alexander Pope (Harry Clarke, 1913, National Gallery of Ireland). [Online] Hyperlink https://twitter.com/ngireland/status/725715381155946496 Accessed 12th March 2018.

The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen (Harry Clarke, 1916, National Gallery of Ireland). [Online] Hyperlink http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_NxfYDdv0Z7Y/SprpNkFSB5I/AAAAAAAAATU/p-3BwIUcMuY/s1600-h/Clarke1a.jpg Accessed 12th March 2018.